South Africa’s online education sector is a burgeoning industry with exciting prospects. However, it is also one that faces many challenges. Since much of the country lacks access to digital resources and quality education, most of these challenges relate to accessibility. One barrier to access involves the language that is used in educational materials – particularly in a country that is already grappling with language and digital literacy issues. This article aims to explore how plain language writing and editing can contribute toward equity in online education.

Understanding plain language

The concept of plain language has been discussed extensively, and there is no shortage of information online regarding what it entails. As laid out by the United States’ (US) Plain Writing Act of 2010, the idea refers to ‘[w]riting that is clear, concise, well-organized, and follows other best practices appropriate to the subject or field and intended audience’ (Plainglanguage.gov 1, n.d.). It may also be helpful to consider plain language from the perspective of what it is not. For instance, De Stadler (n.d.) suggests that the use of the word ‘plain’ is a problem, as it may imply that texts should be ‘dumbed down’. However, this is never the intent of a plain language review or rewrite; rather, it can be thought of as ‘accessible writing’ (De Stadler, n.d.). Additionally, plain language is not an all-or-nothing exercise. Instead, it involves aiming for different degrees of language accessibility, depending on the context (De Stadler, n.d.). For example, a report that is aimed at the executives of a company may have different accessibility requirements to a consumer contract, due to the expected relative experience of the audiences.

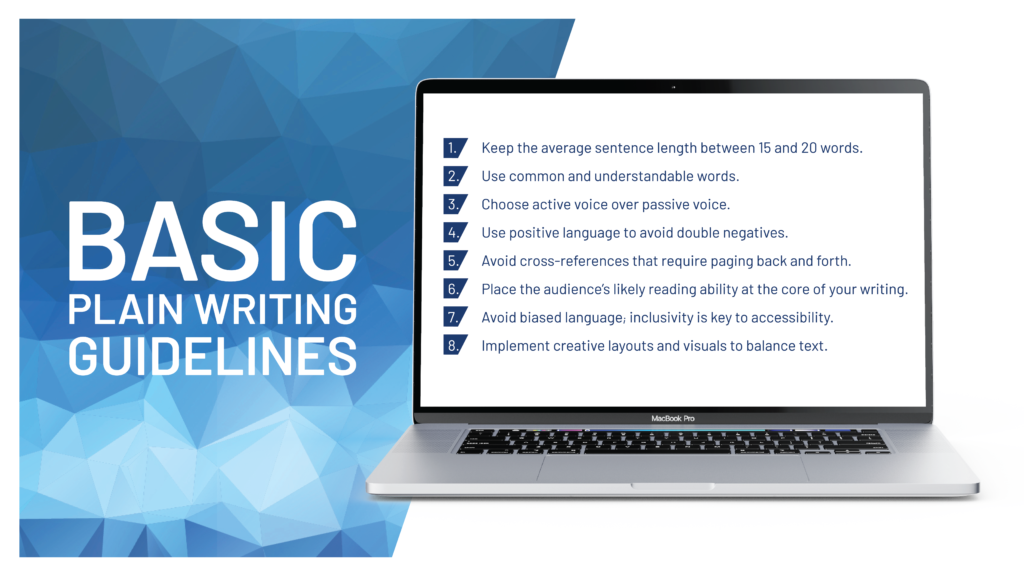

The following image presents a few plain writing guidelines that are cited most commonly by plain language proponents.

However, plain language is so much more than a set of guidelines for writing effective content. In fact, it has evolved into a global movement that places itself at the centre of accessible and equitable communication.

Core identifiers of plain language content include that it helps the reader to ‘find what they need’, ‘understand what they find’ and ‘use what they find to meet their needs’ (Plainglanguage.gov 1, n.d.). In other words, the aim of plain language writing and editing is to take an audience-centred approach to the content. In line with this, content writers and editors worldwide have been adopting the principles of plain language and applying them to all kinds of writing. This has resulted in what some refer to as a ‘movement’, as it has influenced areas that are outside of the typical ‘copywriting’ field – like the drafting of legislation. For example, the US’s Plain Writing Act ‘requires all federal agencies to use clear government communication that the public can understand and use’ (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, n.d.). Furthermore, in the United Kingdom, bodies such as the Plain English Campaign and the Plain Language Commission have been at the forefront of plain language rewriting and training, advocating for the rewriting of tax laws in the country (Plainglanguage.gov 2, n.d.). Laws such as these have a direct impact on every person’s ability to access important information that influences their lives as consumers and citizens.

While there is no singular ‘plain writing’ legislation in South Africa, there has been a movement to include plain language guidelines and definitions in various Acts. For example, the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008 (CPA) and the National Credit Act 34 of 2005 include provisions stating that consumer documents must be written in plain language. Section 22(2) of the CPA states that consumer documents should be written in such a way that ‘an ordinary consumer’ who has ‘average literacy skills and minimal experience’ can comprehend the document ‘without undue effort’. Other legislation that requires the use of plain language in specific fields includes the Long-term Insurance Act 52 of 1998 and the Short-term Insurance Act 53 of 1998 (Coetzee, 2019: 25). There are several other Acts that require the use of plain language writing, and many others in which plain language is referenced. However, these pertain mainly to consumer-facing industries – particularly those that provide financial services (Michalsons, 2009).

The inclusion of plain writing requirements in legislation points to the need for content that is accessible across various contexts. However, as De Stadler (n.d.) suggests, a restrictive approach to plain writing that is based on legal jargon will not yield the desired results. Language comprehension in South Africa is affected by multiple intersecting factors, which means that any writing intended for consumption by a South African audience needs to place accessibility at its core. As such, advancements in legislation constitute only one step toward bridging the language gaps in South Africa (as will be discussed in more detail later in this article).

Language and issues of equity

Historically, South Africa has not prioritised the use of plain language, and our troubled past demonstrates why the impetus for plain writing influences matters of equity directly. When legislation is inaccessible to the public, inequitable Bills can be ratified more easily – as was the case during apartheid. Although it is positive that the passing of legislation post-1994 requires plain writing in matters relating to consumers, ‘efforts at implementing plain English […] generally do not address the needs of people who are in need of access to justice’ (Jensen in Coetzee, 2019: 25). As asserted in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, access to information is a basic human right (Cornelius, 2015: 9). However, when content is inaccessible due to overly complex language and poor structure, the people who may need the information most will be at a disadvantage. In other words, overly complex language can be used as a tool to distance people from understanding the law and other important notices. The term ‘information apartheid’ is used to highlight the segregating effects of a lack of access to information.

One example of these effects comes from an American study of the impact of inaccessible wording in loan documents on African-American loan applicants (Jones and Williams, 2017). In the study, it was found that documentation that is difficult to understand may result in African-American applicants being denied loans more frequently than their white counterparts, which may worsen existing racial disparities in loan granting (Jones and Williams, 2017: 414). The study therefore suggested that plain language could be used in these documents as a way to ‘even the playing field’ for marginalised groups (Jones and Williams, 2017: 412).

As such, ‘plain language gives citizens and consumers better access to their rights, and it combats the information apartheid that convoluted, overly complicated documents generate’ (Willerton in Jones and Williams, 2017: 412). In this way, the accessibility of the language used has an impact on the effectiveness of legislation.

Overly complicated language is not necessarily used on purpose – it can be a result of carelessness, or a lack of training or quality assurance. Similarly, when complex language is used in educational material, it is unlikely to be designed that way intentionally. Instead, it is more likely that content creators and educational platforms have neglected to check whether their content is accessible to their target audience.

Language and education

Before we can discuss how plain language relates to education, it is important to establish how it (along with its implications for accessibility) relates to South Africa specifically. This necessitates a discussion of two of the major barriers to communication in the country: issues surrounding literacy and English as a second language.

1. Language and literacy

When it comes to literacy levels, South Africa appears to fare acceptably in the global ranking. According to World Population Review (2023), South Africa has a literacy rate of 94.60 per cent. However, while this percentage may seem high, the country ranks 113th globally, out of the 155 countries listed. It is vital to remember that comparisons between countries may not be completely accurate, as many countries fail to report their literacy statistics annually, and not all countries define literacy in the same way (World Population Review, 2023).

The 2022 Fact Sheet for Adult Illiteracy in South Africa defines literacy as ‘the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts’ (Khuluvhe, 2022: 2). The document uses the term ‘functional literacy’ to refer to individuals who ‘can engage in all those activities in which literacy is required for effective functioning’, and who are able to ‘use reading, writing and calculation for [their] own and the community’s development’ (Khuluvhe, 2022: 3). By that definition, someone who is functionally illiterate cannot comprehend various forms of communication effectively. Therefore, a functionally illiterate person cannot use the information in these communications to develop themself or their community.

As of 2020, ‘3.7 million adults in South Africa are still illiterate’ (Khuluvhe, 2022: 8). This is relevant to the discussion on complex language, because if we assume that such a significant portion of the South African population is operating on a lower level of literacy, then it is reasonable to expect that complex communications will be less accessible to these individuals. In addition, even people operating with a functional, but somewhat basic, level of literacy may not be able to engage with overly complicated communications effectively. This includes those who are semi-literate, according to Khuluvhe’s definition.

We can apply this information on literacy in South Africa to educational resources. Plain language writing and editing resources cannot be focused on only civic documents that are aimed at the average adult reader. The effort to improve communications must begin with education, so that students attempting to access information can make use of this information fully. If our educational resources are inaccessible to our audiences, then we cannot reasonably expect readers to be prepared to analyse and use documents in other aspects of their lives. This is especially true in today’s context, where the proliferation of online education intersects with issues of digital accessibility.

2. English as a lingua franca in a multilingual country

Another major obstacle to language and education in South Africa is the disparity between individuals’ mother tongue and the language used in educational resources. As of 2018, only 8.1 per cent of the population spoke English inside of their households, while outside of the household, English was spoken by only 16.6 per cent of people (Galal, 2022). In contrast, isiZulu was spoken by 25.3 per cent of the population inside of their households, and by 25.1 per cent outside of the home (Galal, 2022). This serves as an example of how widely other languages are used compared to English. The statistics regarding household usage are particularly interesting, because they suggest that these individuals would be speaking English as a second or third language, assuming that they are able to communicate in English. Even though it is spoken fluently by fewer households than other languages are, English remains the main language of learning and teaching (LoLT) in South Africa.

Again, we must bear in mind South Africa’s legacy of apartheid. During the apartheid era, English and Afrikaans were the LoLTs by law, despite the variety of home languages present in the country. It is within our current post-apartheid context that the Department of Basic Education began efforts in 2011 to improve education in mother tongues, with the idea that access to information may be improved by using these languages in educational resources (Balfour and Wildsmith-Cromarty, 2019: 300). However, models that explain how this shift should be achieved were based on English-language teaching, which posed a problem for educators, as students were still expected to have a relatively high competence in English as a first additional language by the end of Grade 3 (Balfour and Wildsmith-Cromarty, 2019: 300). This remains a challenge, because most learners and teachers in under-resourced South African schools do not speak English as a home language, yet the LoLT – and, therefore, educational resources – typically shifts to English after Grade 3 (Balfour and Wildsmith-Cromarty, 2019: 313). Similarly, higher education in South Africa is dominated by English as the LoLT, with most institutions offering tuition in African languages only as elective modules (Ngidi and Mncwango, 2022: 2).

In light of the country’s context of literacy challenges and disparities in language fluency, developers of educational resources – particularly in higher education – will need to create content that is more accessible to South African citizens. This is necessary for the content to meet the requirements of functional literacy, as outlined by Khuluvhe (2022) – i.e. that students can use the educational resources effectively in order to develop themselves and their communities. Naturally, this need for accessible material then extends to online content providers – particularly given the proliferation of online learning post-Covid-19 (read our article, ‘The digital divide: Overcoming barriers to digital learning in post-Covid-19 South Africa’, for more on this).

In an ideal scenario, the most direct solution to content accessibility in South Africa would be to present documents and resources in the home language of the intended audience. In this scenario, plain language writing cannot be considered a complete solution, as it would still be in English (Coetzee, 2019: 28). Even if educational resources are created using a wider variety of home languages, based on the literacy data discussed by Khuluvhe, these resources would still need to be written in an accessible manner – i.e. plain language strategies could be employed, regardless of the language of the document. However, this is not the linguistic reality of South Africa (Coetzee, 2019: 28), as English is both the lingua franca (common tongue) and the language of commerce in the country (Monyai, 2010: 1).

As such, it is understandable that when students with a low level of English language proficiency are educated in predominantly English, they may experience a number of negative effects. These effects may include (Monyai, 2010: 13):

- poor academic achievement;

- a poor foundation for cognitive development and academic progress;

- a poor self-image and lack of self-confidence; and

- emotional insecurity/anxiety.

As mentioned previously, the accessibility of language has implications for equity among those who lack access to information due to issues such as literacy. If we do not empower our students (both children and adults) with educational content that is accessible to them, they may have difficulty interacting with others in civil society effectively. One example of the effects mentioned comes from a study of black students who use English as a second language and the challenges they face at ex-model C primary schools, conducted by Monyai (2010). The study outlined that many students had come from outlying rural areas and/or townships, with families who had sent them away in hopes of a better education (Monyai, 2010: 1). However, because the students in these circumstances often did not have an existing proficiency in English that was ‘adequate for the purposes of formal learning’, ‘they [did] not succeed or perform well in assessment tasks’ once they began schooling (Monyai, 2010: 1). This example shows the relationship between a lack of proficiency in the LoLT and difficulty learning from the educational resources provided in this LoLT. In turn, such students may struggle with further schooling, which can have lasting negative effects on their lives and social equity.

If we apply these issues to online education, we are left with an important question: In a country where education continues to be a controversial issue, how do we enable students to take part on a global digital stage when the language in our online resources may pose a barrier?

Challenges to implementing plain language

As alluded to, plain language on its own cannot be viewed as a silver bullet for issues of accessibility in general, let alone in online education. However, there are also ways that plain language techniques can be implemented in conjunction with other methods to try to address a few of their shortfalls.

Lack of consensus on definitions

Firstly, as discussed already, there are issues relating to definitions. Defining literacy concretely in the first place can be problematic. For example, we may ask ourselves, ‘If a document is provided only in English and the consumer can read only in Sesotho, will the consumer still be of “average literacy”?’ (Burt in Cornelius, 2015: 13). Even if we restrict the word ‘literacy’ to mean English literacy, and even if we use more restrictive definitions such as Khuluvhe’s, most literacy tests ‘measure academic literacy as opposed to general literacy, and are mainly available in English’ (Cornelius, 2015: 14). As a result, using literacy rates as the sole basis for arguments in favour of plain language may result in those arguments being based on skewed assumptions.

Additionally, while arguments based on multilingualism and second-language speakers do seem to point toward plain language as the standard for texts aimed at these audiences, many plain language guidelines do not necessarily provide direction when it comes to crafting these texts specifically. In fact, most studies on plain language have tested the guidelines only ‘in English with native English speakers’ (Coetzee, 2019: 27). This brings into question the validity of studies claiming that plain English can be used as a solution for problems faced by second-language speakers. There also remains a gap in the research as to whether plain language writing inherently results in improved cognition (understanding of a text) for all readers. Consequently, it is recommended that plain language guidelines be implemented as part of a larger strategy. For example, plain language techniques could be used alongside interventions that provide teachers with training and higher-quality learning materials, so as to ensure the quality (and accessibility) of these materials (Balfour and Wildsmith-Cromarty, 2019: 312).

‘Dumbing down’ important concepts

There are those who argue that plain language cannot be implemented as a blanket approach across all scenarios. These arguments point to issues such as oversimplification, which may result in education not being as rigorous as it needs to be in order to produce the desired outcomes. However, because plain language at its core requires the author to retain all meaning, techniques such as including definitions and glossaries can be used to ensure that technical terms and jargon are still learned, and that the content is pitched at an appropriate level. Techniques such as these also address concerns that plain language may not expand students’ academic vocabularies. Nonetheless, vocabulary development is certainly a risk if plain language is implemented too broadly. Here, the importance of individual contexts is key.

The ideas of technical knowledge and development relate to the issue of consensus among plain language practitioners. In other words, is plain language about simplifying a text as much as possible, at the expense of elaboration? As an approach to this issue, we can recommend that any plain language strategy should take an individualised approach. As such, in the case of social justice and education, which requires ‘critical thought that moves toward critical action’, it may be necessary for writers to ‘take a human-centered design approach to plain language rather than a usability approach’ (Jones and Williams, 2017: 427). For example, in the online educational context, the accessibility strategy used in a more practical learning activity, such as ‘create a monthly budget’, will differ from the strategy implemented in a high-level academic activity, such as ‘compare and contrast different learning theories’. With a practical outcome like creating a budget, it would likely be beneficial to make use of simple instructions with accessible explanations. In contrast, the ability to ‘compare and contrast’ different concepts requires a more comprehensive understanding of the topics covered, and it implies an academic context in which students must be able to think critically. Here, the human-centred approach would suggest a use of plain writing that does not sacrifice the information needed to address this high-order outcome.

The burden of implementation

Due to the need for specialised writing skills, along with a lack of consensus about specific guidelines, the burden of implementation for plain language can be heavy. In order to achieve a solution that is catered toward its specific context, and that does not fail to meet educational outcomes, specialised technical knowledge will be required (Cornelius, 2015: 14). This may require special training, which could be problematic in institutions such as government organisations or schools, where resources are stretched thin already. For example, in the case of accessible learning materials to give to students, it may be necessary to update existing materials using plain language techniques, among others, to make them easier to understand. However, this may be a challenging task for staff such as teachers, who are already burdened by other challenges, and who lack the necessary training in writing and layout.

This is where the plain language movement comes in. The more that we see writers, content developers and editors using plain language principles in their work, the more the pool of information and training on the subject grows. This pool of resources should be leveraged by various stakeholders, including private instructional designers and even government, to create a more equitable learning environment for the modern student.

Conclusions

The discussion around plain language usage in educational resources can be a contentious one, with some confusion as to how it can even be implemented. The idea of ‘blanket implementation’, without proper guidelines on the nuances of plain writing, could result in oversimplified content. This is why plain writing and editing that balances accessibility with educational value can be viewed as somewhat of an art. While it may be difficult to bring this ‘art’ into all contexts, digital content providers are well situated to take advantage of the movement to produce content that truly achieves what it sets out to do. This is in part due to their access to professionals with experience in this realm. Of course, implementing plain language techniques constitutes only one step in the journey to bringing information and education to those who cannot access it. Nevertheless, it is an important step, since it has an impact on the foundations upon which other interventions will be based. As has been recommended, solutions will need to take an individualised, context-specific approach, and practitioners should consider creative ways of presenting information to make it more accessible.

Indeed, as Sarah Richards (in Metts and Welfle, 2020) so aptly puts it, ‘if the words you write for something aren’t accessible to everyone, then you’ve made a design choice that prevents people from using that thing’. In this way, plain language writing and editing is a choice not only for more effective content, but also toward equitable content – and, in the case of the EdTech industry, toward equitable education.

Want to know more? Here are a few useful resources:

- Plain language templates and training: https://centerforplainlanguage.org/learning-training/templates-tools-training/

- Plain language checklists: https://www.plainlanguage.gov/resources/checklists/

Bibliography

Balfour, R. J. and Wildsmith-Cromarty, R. (2019), ‘Language learning and teaching in South African primary schools’. Language Teaching 52(3): 296–317.

Coetzee, S. (2019), ‘The comprehensibility of plain language for second language speakers of English at a South African college of further education and training’. Unpublished dissertation (MA), Cape Town, South Africa: Stellenbosch University.

Cornelius, E. (2015), ‘Defining “plain language” in contemporary South Africa’. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics 44: 1–18.

Cutts, M. (2013), Oxford Guide to Plain English. 4th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

De Stadler, E. ‘In Search of Plain Language’. Novation Consulting [website] <https://novcon.co.za/2016/10/13/in-search-of-plain-language/> accessed 12 January 2023.

Galal, S. (2022), ‘Distribution of languages spoken by individuals inside and outside of households in South Africa 2018’. Statista [website] <https://www.statista.com/statistics/1114302/distribution-of-languages-spoken-inside-and-outside-of-households-in-south-africa/> accessed 8 September 2022.

Jones, N. N. and Williams, M. F. (2017), ‘The Social Justice Impact of Plain Language: A Critical Approach to Plain-Language Analysis’. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication 60(4): 412–429.

Khuluvhe, M. (2022), Fact Sheet: Adult Illiteracy in South Africa. Pretoria: Department of Higher Education and Training.

Mateeva, N., Moosally, M. and Willerton, R. (2017), ‘Plain Language in the Twenty-First Century: Introduction to the Special Issue on Plain Language’. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication 60(4): 336–342.

Metts, M. J. and Welfle, A. (2020), Writing is designing: Words and the user experience. New York, NY: Rosenfeld Media.

Michalsons [website] (2009), ‘Legislation that requires Plain Language’. <https://www.michalsons.com/blog/legislation-that-requires-plain-language/2354> accessed 25 July 2022.

Monyai, S. C. (2010), ‘Meeting the Challenges of Black English Second-Language South African Learners in Ex-Model C Primary Schools’. Unpublished dissertation (MA), Pretoria, South Africa: University of Pretoria.

Ngidi, S. A. and Mncwango, E. M. (2022), ‘University students’ perspectives on an English-only language policy in Higher Education’. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa 18(1): 1–5.

Plain Language Association International [website] ‘What is plain language?’ <https://plainlanguagenetwork.org/plain-language/what-is-plain-language/> accessed 12 January 2023.

Plainglanguage.gov 1 [website] ‘What is plain language?’ <https://www.plainlanguage.gov/about/definitions/> accessed 27 June 2022.

Plainglanguage.gov 2 [website] ‘Plain Language: Beyond a Movement’. <https://www.plainlanguage.gov/resources/articles/beyond-a-movement/> accessed 27 June 2022.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration [website] ‘The Plain Writing Act of 2010’. <https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/plain-writing-its-law/plain-writing-act-2010> accessed 27 June 2022.

World Health Organization [website] ‘Tactics to apply to make your communications understandable’. <https://www.who.int/about/communications/understandable/plain-language> accessed 27 June 2022.

World Population Review [website] (2023), ‘Literacy Rate by Country 2023’. <https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/literacy-rate-by-country> accessed 16 January 2023.

Register of statutes

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.

Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008 (CPA).

Long-term Insurance Act 52 of 1998.

National Credit Act 34 of 2005.

Plain Writing Act of 2010.

Short-term Insurance Act 53 of 1998.

Image credits

EDGE Education (Pty) Ltd